Debugging the Culture, Not Just the Code, to solve Malaria

We went to Mozambique in Sub-Saharan Africa to deploy an SMS-based Malaria platform. We realized that to save lives, we first had to put down our laptops and pick up a deck of cards.

The Hardware Graveyard

The Context: Mozambique faces a brutal public health reality: 3 doctors per 100,000 people. Malaria is a top killer of children under 5.

The Initial Observation: When our team arrived at the Chicuque Rural Hospital, we saw a disturbing trend: The "Hardware Graveyard." $100,000 worth of donated medical equipment sat unused and broken.

The Real Challenge: The problem wasn't a lack of "Stuff" (equipment/medicines exist). The problem was Access and Awareness.

Physical Barrier: Patients walked hours to reach a clinic, often too late.

Cognitive Barrier: People didn't know when to seek help. They couldn't identify the early symptoms of Malaria.

Medical equipment graveyards in low-resource hospitals. Medical devices designed for use in high-resource settings often fail when used in harsh environmental conditions found in low-resource hospitals; because user instructions or spare parts are not accessible, broken devices remain in equipment graveyards like those pictured here in Malawi. Therefore, rigorous evaluation protocols are needed to identify medical devices that are effective, affordable, rugged, and easy to use in low-resource settings. (Photo credit: Brandon Martin, 2016)

The App Wasn’t Enough

We did what many organizations in this sector do: We held a Hackathon. We mobilized US university students to build "Ola Health"—a brilliant SMS-based system allowing villagers to hail a Community Health Worker (CHW) like an Uber.

The Reality Check: The tech worked perfectly. But in the field, usage was low. Why? Because an "Uber for Malaria" is useless if the user doesn't know they are sick. We had built a solution for a problem the user hadn't diagnosed yet.

Coke, Church, and Card Games

Dhairya Pujara with Community Health Workers in a remote village in Mozambique

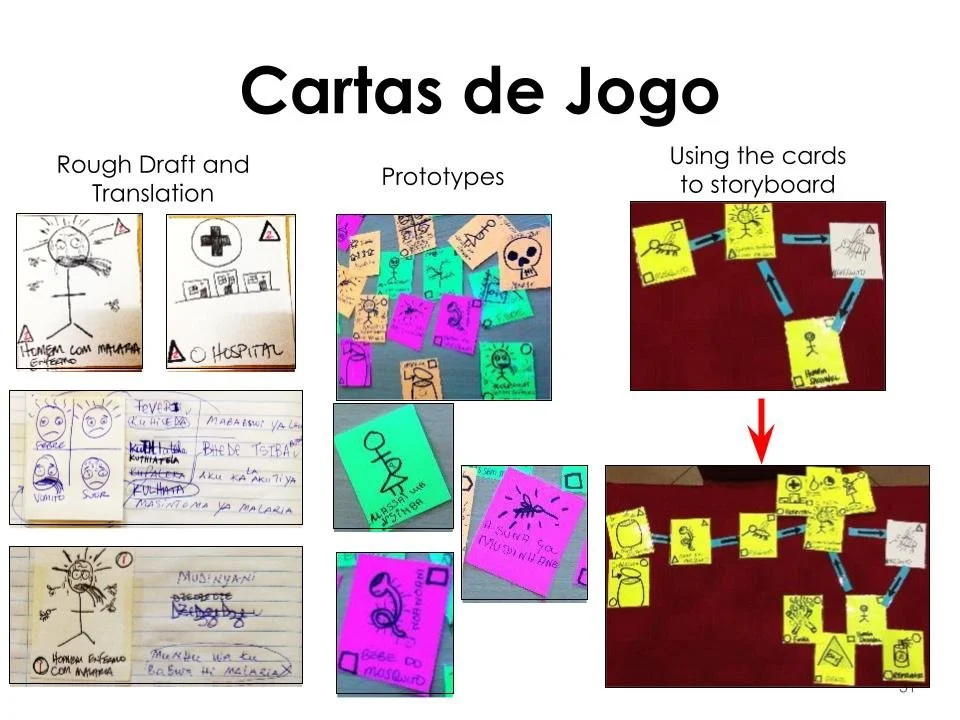

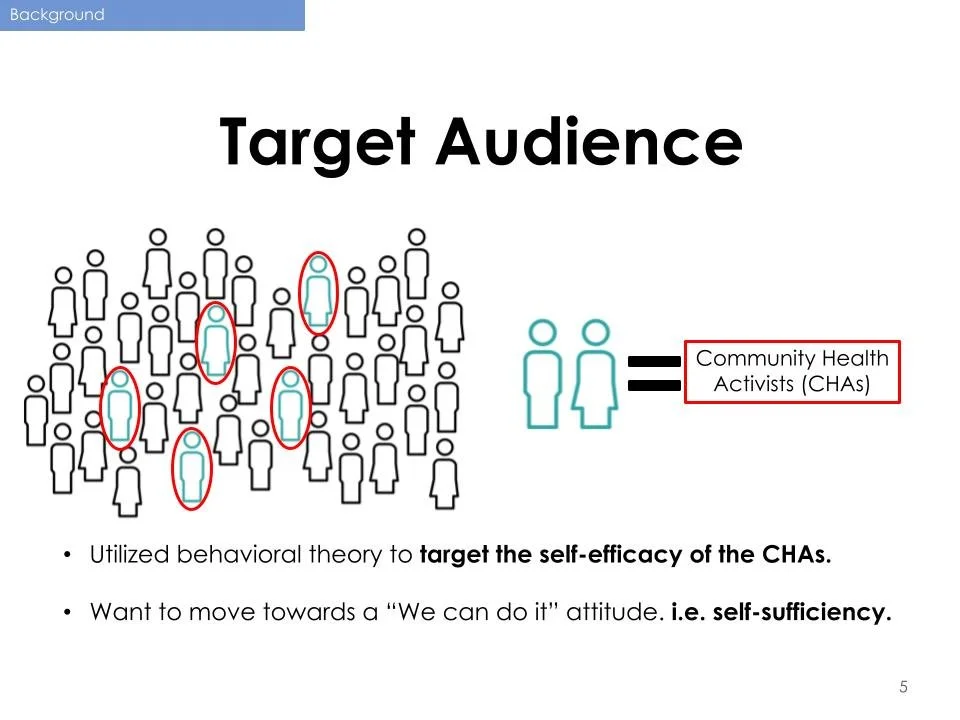

We paused the code deployment and started Ethnographic Research. We lived in the community to find the "Hidden Universals"—the things that everyone had access to, regardless of poverty.

We found three things:

A Cell Phone (Dumbphone, not Smart).

A Can of Coca-Cola (Supply chains that worked).

A Deck of Cards (The universal pastime).

The Breakthrough: We realized that the "Card Game" was our Trojan Horse. Villagers spent hours playing cards. If we could gamify the education inside that habit, we could trigger the demand for the SMS service.

The Hybrid Intervention

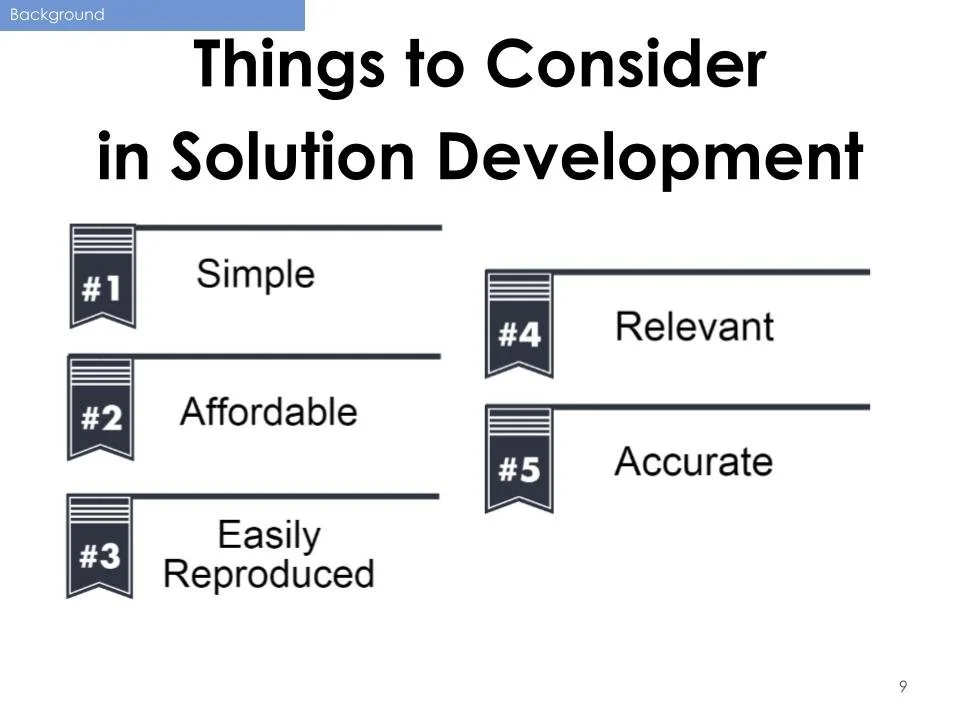

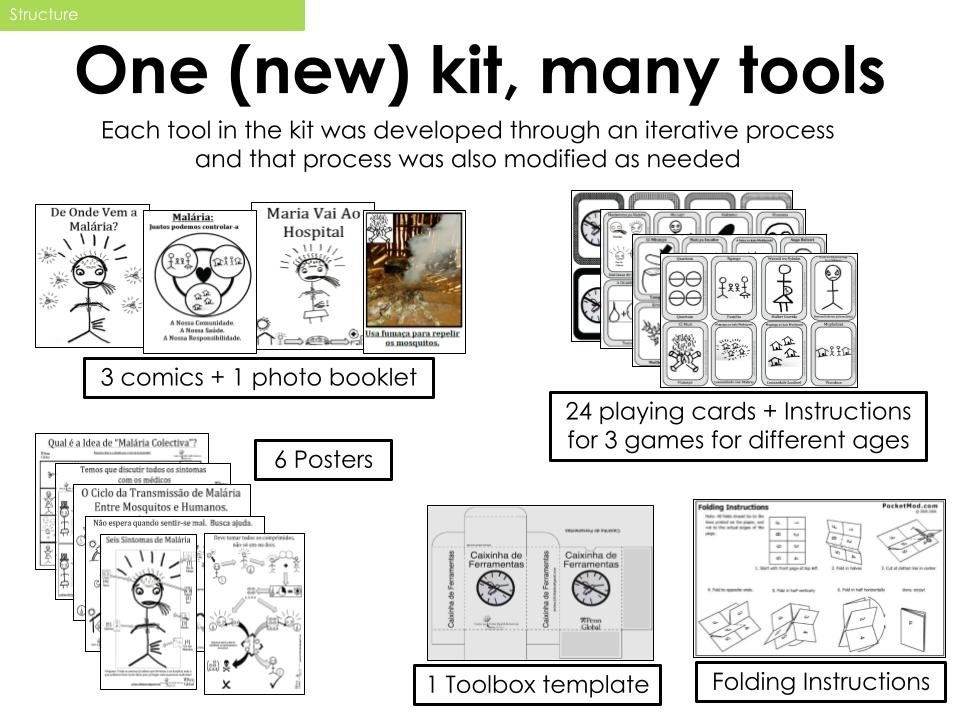

We designed a two-part system that combined Low-Tech Digital with High-Touch Analog.

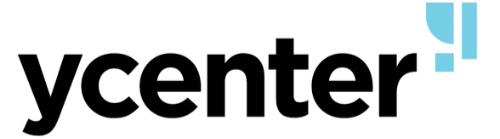

1. The Analog Trigger (The Card Game)

We co-created a card game with local artists and volunteers. The game mechanics taught players how to identify Malaria symptoms versus the common flu.

Result: It turned "Education" into "Play." It created the Trigger.

2. The Digital Fulfillment (Ola Health)

Once a player identified a symptom, they used the SMS App to alert the local Community Health Worker.

Workflow: The CHW arrives at the doorstep -> Administers Rapid Test -> Logs Data via SMS -> Dispenses Meds immediately.

From Malaria to Maternity

The project proved that Human-Centered Design creates infrastructure, not just interventions.

3

Villages Adopted The pilot communities successfully integrated the SMS system into their daily health flow.

Zero

Learning Curve By using existing habits (SMS and Card Games), we eliminated the need for complex training.

Scale

Platform Agnostic The community trust built allowed the system to expand beyond Malaria into Prenatal Care and Maternal Health tracking.